Lawrence Durrell

Chronology of publications

1912 Lawrence Durrell born, 27 February

1935 Pied Piper of Lovers [novel]

1936 Panic Spring [novel]

1937 The Black Book [novel]

1943 A Private Country [poems]

1944 Prospero’s Cell [Corfu]

1945 Cities, Plains and People [poems]

1946 Cefalû [novel] (as The Dark Labyrinth 1961)

1948 Seeming to Presume [poems]

1950 Sappho [play]

1952 A Key to Modern British Poetry [lectures]

1953 Reflections on a Marine Venus [Rhodes]

1955 The Tree of Idleness [poems]

1956 Selected Poems

1957 Bitter Lemons [Cyprus]

Esprit de Corps [sketches of diplomatic life]

Justine [novel]

White Eagles Over Serbia [novel]

1958 Balthazar [novel]

Mountolive [novel]

Stiff Upper Lip [diplomatic sketches]

1959 Clea [novel]

Pope Joan [novel, translation]

Complete Poems (new edition, 1980)

1962 Justine, Blathazar, Mountolive, Clea published as The Alexandria Quartet

1963 An Irish Faustus [play]

1965 Acte [play]

1966 Sauve Qui Peut [diplomatic sketches]

Esprit de Corps, Stiff Upper Lip, Sauve Qui Peut published 1985 as Antrobus Complete

The Ikons [poems]

1968 Tunc [novel]

1969 Spirit of Place [letters, essays]

1970 Nunquam [novel] Tunc, Nunquam published 1974 as The Revolt of Aphrodite*

1973 Vega [poems]

1974 Monsieur [novel]

1977 Sicilian Carousel [Sicily]

1978 Livia [novel]

The Greek Islands [travel]

1980 A Smile in the Mind’s Eye [philosophy]

1982 Constance [novel]

1983 Sebastian [novel]

1985 Quinx [novel] Monsieur, Livia, Constance, Sebastian, Quinx published 1992 as The Avignon Quintet

1988 The Durrell-Miller Letters

1990 Caesar’s Vast Ghost [Provence]

Durrell dies, 7 November

Lawrence Durrell was born on 27 February 1912 in Jullundur (also variously spelt Jalandhar) near Lahore in north-west India, the son of Lawrence Samuel Durrell and his wife Louisa Florence (née Dixie). His father was a civil engineer. His parents had both been born in India: Durrell’s mother put it succinctly when she said ‘Most people talked of home and meant England, when we said home we meant India.’ Durrell’s maternal grandfather had been born there in 1854, but on his father’s side his grandfather (born in England in 1851) had not arrived in India until 1876. Durrell’s father’s boss, Cecil Henry Buck, married Durrell’s aunt, and wrote Faiths, Fairs and Festivals of India (1917).

Durrell’s father, the son of a Suffolk-born army sergeant, was an engineer working for the Indian railway companies until 1920, when he established Durrell & Company at Jamshedpur, in Bihar province, where he built a hospital and the Tata Iron and Steel Works. (Founded by Jamsetji Tata in 1868, the Tata group is today a global enterprise headquartered in India, comprising over 100 operating companies in more than 100 countries across six continents.)

Durrell senior’s success was short-lived, however, as he died eight years later at the age of forty-three. Durrell’s earliest memories were of villages in Burma and present-day Bangladesh, until, in 1918, his family moved to Kurseong in the north-east of India, in the triangle tucked under the Himalayas in the lap of Nepal, where his father was responsible for the maintenance of railways, including the Darjiling line: ‘The track ran through landscapes of dreams… You had the snows and the mists always opening and closing upon sheer precipices’. It was in the north-east, however, in Kurseong, that the young Lawrence Durrell began his lifelong attempt to locate his life of exile between the memories of his childhood and his colonial views of ‘home’:

“under the Himalayas. The most wonderful memories – a brief dream of Tibet until I was eleven. Then that mean, shabby little island up there wrung my guts out of me and tried to destroy anything singular and unique in me”.

The reference to ‘that mean shabby little island’ indicates Britain, which Durrell disliked and to which he often referred as ‘Pudding Island’.

Like many Anglo-Indians, Durrell senior maintained a mental landscape of ‘home’, an England which at that stage he had never seen, but whose values and significance were part of the nineteenth-century colonial baggage, a lien on an idea of empire and history which was only partly real, and almost impossible to articulate: homeland.

Lawrence Durrell was educated at St Joseph’s College, Darjeeling (he spelt it ‘Darjiling’) until, at his father’s insistence, he was sent to school in England – first at St Olave’s and St Saviour’s Grammar School in Southwark and then St Edmund’s, Canterbury, experiences which provided a solid and significant basis for his first three novels with their medieval substructure. One of the most significant encounters during these years was his discovery, in Southwark Cathedral, of a group of recently recoloured and regilded tombs: ‘in form, proportion, heaviness of decoration and unapologetic brightness of colour – particularly of colour – they at once brought India to his mind’.

Durrell claims to have deliberately failed the entrance exams to university. He settled in London, where he befriended the poet, critic and collector John Gawsworth. He spent much time in the Reading Room of the British Museum (today, the British Library) where he read voraciously. He earned a precarious living as a rent-collector, a railway porter, an apprentice racing driver and, less improbably, playing jazz piano in a night-club (and indeed composing and selling jazz songs using his mother’s surname as a partial nom-de-plume), running a photographic studio and, later, writing drama criticism.

Durrell married Nancy Myers, an art student, and they lived at first in the Sussex countryside at Loxwood with their friends George and Pam Wilkinson, setting up the Caduceus Press to print Durrell’s first poems.Then in 1935 they decided, on the basis of a small income which he received from his father’s estate, to follow the Wilkinsons’ example and live economically on the island of Corfu in the Ionian Sea off north-west Greece. At this stage, Durrell had published nothing except a few small collections of poetry, Quaint Fragment (1931), Ten Poems (1932) and Transition (1934) and, in 1933, under the pseudonym ‘Gaffer Peeslake’, a satire of Shaw’s Black Girl entitled Bromo Bombastes.

The move to Corfu was highly significant since it was there that he conceived his entire life’s work as a novelist; he had written his first novel, Pied Piper of Lovers and corrected the proofs after arrival in Corfu. He wrote his second novel, Panic Spring in Corfu and began his third, The Black Book. His years in Corfu (1935-39) were recorded subjectively in the poetic Prospero’s Cell.

The move to Corfu was also significant because Lawrence persuaded his widowed mother (who, after her husband’s death had moved her family to England) to move to Corfu with her younger children Leslie Stewart (1917 – 81) , Margaret Isabel Mabel (Margot, 1919-2007) and Gerald Malcolm (1925 – 1995).

This led to her youngest son, Gerald, also conceiving his life’s work during his formative years, largely under the guidance of Theodore Stephanides. Gerald recorded his own impressions of Corfu in three books (known collectively as the Corfu Trilogy): My Family and Other Animals, Birds, Beasts and Relatives and The Garden of the Gods. Durrell also made the long-standing friendship of Dr Theodore Stephanides (1896-1982) – who became an unofficial tutor to Gerald – and the Armenian writer Constant Zarian.

In Corfu Durrell read, and was heavily influenced by, Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer . Miller was in Paris at that time and in 1937 Durrell and Nancy made a prolonged visit to Paris where they befriended Miller, Anaïs Nin and Alfred Perlès, the photographer Brassaï and the painter Hans Reichel. With Miller and Perlès, Durrell edited a magazine, The Booster, which had been a quite respectable house organ of the American Golf and Country Club but which, under their direction, renamed Delta, became an avant-garde vehicle for their own writing.

In Corfu Durrell conceived his entire life’s work, which he subsequently set out in a letter to T S Eliot:

agon pathos anagnorisis

The Black Book The Book of the Dead The Book of Time

the dislocation the uniting the acceptance and death

On the outbreak of war in 1939 Durrell and Nancy moved initially to Athens, where they befriended two leading figures of Greek literature, George Seferiades [Seferis] and George Katsimbalis. During this period their child, Penelope Berengaria (1940-2010), was born. Durrell worked briefly at the Institute of English Studies in Kalamata, before evacuating to Alexandria (Egypt).

During World War II, Durrell worked in Egypt as a press officer and also contributed a humorous column to the Egyptian Gazette. He became involved with a group of poets known collectively as ‘Personal Landscape’. His marriage broke up and Nancy and Penelope went to Jerusalem, where Nancy met and eventually married Edward Hodgkin. Durrell met and subsequently married Eve Cohen, an Alexandrian Jewess.

After the war Durrell and Eve went to Rhodes, one of the Dodecanese Islands which were in the process of being transferred to the state of Greece: Durrell was Public Information Officer, and the experience resulted in his book Reflections on a Marine Venus. Subsequent postings took him to Belgrade (which gave rise to the humourous ‘sketches of diplomatic life’ featuring ‘Antrobus’) and Argentina, where he lectured at the university of Cordoba (the result of which was his Key to Modern Poetry). During this period his second daughter, Sappho-Jane (1950-1985), was born to Eve.

In 1953 Durrell, who had been living in Cyprus and teaching at a school in Nicosia, took up his final diplomatic posting as press officer (and editor of the Cyprus Review) during the controversial enosis crisis (which he described in Bitter Lemons). With the disintegration of his marriage to Eve, Durrell began a relationship with another Alexandrian Jewess, the novelist and translator Claude-Marie Vincendon, who became his third wife.

After leaving Cyprus, Durrell and Claude settled firstly at a mazet in the south of France, where they befriended Richard Aldington, and later at his final home, in Sommieres. Claude died unexpectedly on 1 January 1967.

Durrell’s only other official assignment came in 1974, when he taught a course on modern literature at the California Institute of Technology. In that same year he married for the fourth time, to Ghislaine de Boysson (a former Dior model). The marriage was short-lived and acknowledged on both sides to have been a mistake.

Durrell’s subsequent life was lonely and subject to fits of depression, reflected in the novels Tunc and Nunquam. Nevertheless he embarked on his most ambitious literary project in the writing of a ‘Tibetan novel’ which became the Avignon Quintet. In 1986 he met Francoise Kestsman, a Franco-Polish writer and translator, who became his companion (but whom he never married).

Near the end of his life Durrell summed up his loneliness, caused partly by his circumstances as a professional diplomat, partly by his own family circumstances and by the perennial (perhaps inescapable) exilic nature of the writer:

“My life has been tremendously lonely. I’ve always been catapulted into jobs, and so on and so forth, where it took you three or four years to make friends, and always with people I didn’t want to make friends with. I was uninterested so to speak, without being particularly unhappy. I had no club life, no bar-room, no bistro, except in Paris. In the jobs I had I couldn’t have adopted a bistro … that would have been bad for the job, so I was cut off into suburbia, you can imagine what hell that is… It’s been superficially very mouvementé, but I’ve never had a foyer, a hearth, a home. Every time I’ve tried to build one the British came along and put a bomb up my arse.”

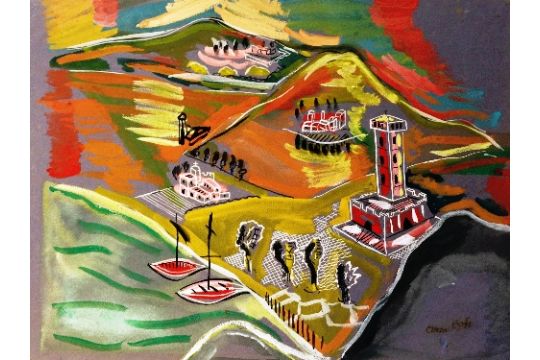

In addition to writing, Lawrence Durrell was also an accomplished painter, using the pseudonym OSCAR EPFS, under which he held several exhibitions. The illustration below is an abstract, by Epfs/Durrell, offered for sale in 2016 at $900 by a UK bookseller with the following description:

“Float mounted and framed together in a black wooden frame. Oil and water on grey paper. Two sheets, each approx: 24 x 32 cm. Each sheet signed as Epfs. Durrell mounted an exhibition as a vehicle for one of his many alter egos, Oscar Epfs in Paris at the Librairie Marthe Nochy in 1970. In terms of pure commerce it was something of a failure: a mere handful of the works were sold. But Durrell apparently revelled in the failure. He was however quite serious about his painting, following Henry Miller in the pursuit, and continued making pictures until his death.”

This “Sailing boats and Greek Buildings” (1964) was sold in 2015 by Cottees Auctions who are also offering “Two Sailing Boats and Churches” and other works by Epfs/Durrell.

This “Sailing boats and Greek Buildings” (1964) was sold in 2015 by Cottees Auctions who are also offering “Two Sailing Boats and Churches” and other works by Epfs/Durrell.

THEODORE STEPHANIDES: A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY

[This biography is an edited version of the text which appears in Theodore Stephanides’ Autumn Gleanings: Corfu Memoirs and Poems 2011]

For books by Theodore Stephanides which are available for purchase, see the PUBLICATIONS FOR SALE page.

Theodore Philip Stephanides was born on 21 January 1896 in Bombay, India, where his father, a native of Thessaly, worked in the Indian Civil Service. His mother was English, and he had both English and Greek as his first languages. When his father retired in 1907 the family moved to Corfu, which was to be the venue for Theodore’s remarkable meetings with the brothers Lawrence and Gerald Durrell in the 1930s, providing the basis for the memoirs printed here verbatim for the first time.

During the first world war, which began when he was eighteen years of age, Theodore served as a gunner in the Greek army on the Macedonian front, following which he saw service in the disastrous Anatolian campaign of 1919-22. His wartime experiences were not very successful, but the accounts of his service are typical not only of his own wry humour in reporting them, but also of the way in which his acquaintances relished the bizarre situations in which he found himself. Alan Thomas, who himself became a close friend of Stephanides, relates that the trainee gunner, given the task of firing a test-shot, ‘worked out the bearings over and over again with his habitual scientific accuracy. The great moment came, the gun fired, and the projectile landed upon a tent, belonging to the medical corps, in which a surgical operation was in progress… “I am probably the only doctor”, Theodore is accustomed to recall with a smile, “who has dropped a shell into an operating theatre!”.’ His experience in the Anatolian campaign was no less undistinguished. His commanding officer gave him the task of leading the entry into Smyrna on a white horse. ‘I had learned to ride, but I would not consider myself an expert horseman… As I was riding at the head of the column, an old woman darted out of a side street and started to hurl eau-de-Cologne about. The horse… became most upset about it and was acting more like a circus horse than a charger. I only managed to stay on because my feet had become wedged in the stirrups. The column had to break ranks to try to calm him down, but he was so upset that eventually the commander decided that it would be unwise to let him take part in the rest of the triumphal entry. So while the column marched through the main streets with bands playing and people cheering and so forth, I was forced to slink through the back streets on my white horse, both of us, to add insult to injury, by now smelling very strongly of eau-de-cologne… I have never really enjoyed horse-riding since then.’

In 1922 Theodore went to Paris to study medicine, and to specialise in radiology, one of his professors being Marie Curie. The 1930s saw him practising in Corfu as a radiologist, and marrying Mary Alexander (a grand-daughter of a former British consul in Corfu), with whom he had one daughter, Alexia. These years also saw him developing his skills as a freshwater biologist, and in the years 1938-39 he conducted significant work for the anti-malaria campaign in Salonika and Cyprus, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. At this stage he had already written his scientific magnum opus, a treatise on the freshwater biology of Corfu, commissioned in 1936 by the Greek government, which was eventually published in 1948, and had been credited with the discovery of three microscopic water organisms, Cytherois stephanidesi, Thermocyclops stephanidesi and Schizopera stephanidesi. As is evident from his memoirs of Corfu, Stephanides was also an astronomer, and is the only person to have named after him not only three of nature’s smallest water-creatures but also a crater on the moon (‘Römer A’ is unofficially named ‘Stephanides crater’).

During the second world war Theodore was a medical officer with the Royal Army Medical Corps in the African western desert, Sicily and Crete. In these years he renewed his acquaintance with Lawrence Durrell who was working in Alexandria and Cairo, and his experiences in Crete led to the publication of his account of the campaign there, with a foreword by Durrell. His parents were killed during the German bombardment of Corfu, but his wife and Alexia had been taken to safety in England and, for some time, lived with the other members of the Durrell family who had returned from Corfu to Bournemouth at the outbreak of war.

At the end of the war, Theodore rejoined his family and, from 1945 until his retirement in 1961, worked as a radiologist at St. Thomas’s Hospital in the London borough of Lambeth. It was during this period that his remarkable flowering as a ‘man of letters’ occurred, with three volumes of poetry, several volumes of translation of the Greek poet Kostes Palamas (in collaboration with George Katsimbalis), a treatise on the microscope and other works, some of them still unpublished. He continued to write and undertake research, appearing with Gerald Durrell in the latter’s BBC documentary on Corfu, The Garden of the Gods in 1967, and working on a proposed but unrealised collaboration with Lawrence Durrell on the history of the Karaghiozis shadow-puppet, which they had first encountered in Corfu in the 1930s. He died on 13 April, 1983.

But these bare facts of his career hardly reflect Stephanides the man. If, for example, one were to compile a ‘Collected Works of Theodore Stephanides’ it would present a remarkably eclectic and wide-ranging series of topoi. Stephanides was a poet; he was a translator; he was a scientist; he was a traveller. And he wrote widely and deeply in all these epiphanies.

Although he began his work as a translator early in life, with two volumes of Greek poetry in 1925/26, with his lifelong collaborator George Katsimbalis, his main contribution to the appearance in English of the poetry of Kostes Palamas was not to occur until after his retirement in 1961. Katsimbalis himself said that his own contribution was unnecessary, since Stephanides had sufficient command of both Greek and English, but Theodore seems to have felt a need for a second opinion from someone steeped in Greek literature, and his volumes, whether or not Katsimbalis contributed much to the translations, appeared under both their names.

Nevertheless, the published work, however varied it may be (as our bibliography indicates), gives only some of the flavour of the man who made such an impact on Lawrence Durrell and Gerald Durrell. Lawrence’s The Greek Islands, and Gerald’s Birds, Beasts and Relatives (‘in gratitude for laughter and for learning’) and The Amateur Naturalist were all dedicated to Theodore, as was Lawrence’s as yet unpublished novella, ‘The Magnetic Island’: ‘dedicated to Doctor Theodore Stephanides of the island of Corfu in memory of four years of a charmed friendship’. Gerald’s dedication of The Amateur Naturalist is even more explicit: ‘This book is for Theo (Dr Theodore Stephanides) my mentor and friend, without whose guidance I would have achieved nothing’. For a very obvious but regrettable reason, Gerald is almost completely ignored in the memoirs. This, one assumes, is because Stephanides was trying to record his adult friendship with Lawrence, who was so clearly a writer-in-the-making, whereas Gerald was, at that time, little more than an impressionable child. Nevertheless, readers of My Family and Other Animals, in which Theodore is portrayed so warmly, affectionately and humorously, will regret that there is no mirror-image by Theodore of Gerald.

As Gerald recorded in his introduction to Island Trails, Theodore ‘strolled into my life, tweed-suited, trilby-hatted, his walking stick with its tiny net on the end, his bag of test tubes and bottles slung on his hip, his beard twinkling in the sun; a sort of walking hirsute encyclopaedia…. To me, just starting to explore and learn about the world I lived in, to have Theodore as guide, philosopher and friend was one of the most important things that have happened to me in my life.’ Elsewhere, Gerald wrote of their first meeting ‘He had a straight, well-shaped nose; a humorous mouth lurking in the ash-blond beard; straight, rather bushy eyebrows under which his eyes, keen but with a twinkle in them and laughter-wrinkles at the corners, surveyed the world.’ At the same time, Lawrence was recording a ‘very Edwardian face – and perfect manners of Edwardian professor. Probably reincarnation of comic professor invented by Edward Lear during his stay in Corcyra. Tremendous shyness and diffidence. Incredibly erudite in everything concerning the island. Firm Venizelist, and possessor of the driest and most fastidious style of exposition ever seen… Theodore is always being arrested as a foreign agent because of the golden beard, strong English accent in Greek, and mysterious array of vessels and swabs and tubes dangling about his person.’[7] And when Henry Miller met him in 1939 he thought ‘Theodore is the most learned man I have ever met, and a saint to boot.’

Introducing Stephanides’ ‘Synoptic History’ of Corfu, John Forte referred to him as ‘an integral part and parcel of the island of Corfu and could in fact be described as a Corfiot institution’. Although he had left Corfu at the outbreak of the second world war, returning only infrequently, the island had been an inspiration to the young Stephanides, as it was in turn to the young Gerald Durrell (they were of very similar ages when they made their ‘landfall’ here) and this is clear in the many references to the island in Stephanides’ poems, and, of course, explicit in his memoir of Lawrence Durrell at Kalami and Palaeocastritsa.

Behind the author of these fifteen volumes and articles in learned journals is the character who shyly appears within the pages of The Corfu Trilogy and perhaps one thinks one ‘knows’ him because Gerald brought him – his scholarship worn so lightly, his curiosity and passion for the world about him, his sense of humour – into such brilliant relief. The brief (one might almost say ‘cameo’) appearance in Gerald’s television programme The Garden of the Gods serves to confirm both his eminence and his humanity, the latter quality shining through the poems published here. But what shines through Gerald’s and Lawrence’s remembrances of this astonishing man is his high intelligence married to a phenomenal curiosity. Theodore was, on occasions, not only a fund of information and insight, on a range of scientific topics, but also a very funny man whose humour belied the three-piece suit in which, we are told, he was habitually garbed.

As a poet, Stephanides was idiosyncratic to the extreme. His poetic style is highly dated, and seems to have its main affinity with the Edwardian and Georgian poets in England in the period 1900-1930. (Ian MacNiven tells us that Lawrence Durrell gave Stephanides copies of poems by Hilaire Belloc, Laurence Binyon, Walter de la Mare, John Drinkwater and Siegfried Sassoon, on which Marios Byron Raizis comments that ‘this is indicative of the kind of poetry that Stephanides liked to read and, of course, to try to emulate. Durrell did not attempt to make him write like Eliot, Pound, Auden, himself, nor like the current Modernists’.)

One might have reservations about the metre, diction and rhyming of the poems, but there are distinct characteristics which make them still rewarding. The themes which Stephanides continually revisited were: nature and natural phenomena (both in the romantic sense and with his scientist’s eye); the interaction between landscape and love; and of the absurdity of human behaviour. Many of his observations of London-at-night are particularly touching, but some of his most affective lines are the shortest – his ‘quatrains’ and ‘distichs’: what Lawrence Durrell would have called ‘squibs’, deflating pomposity and arrogance, especially in relation to politicians. And there are other humorous or mischievous pieces such as ‘Prue the Prudent Vampire’, the medley of ‘The Wreck of the Schooner Hesperus’ and ‘The Tempest’. Most moving of all, perhaps – because many of these pieces were written in old age – is the realisation and acceptance of the transience of human life, and especially of human love.

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THEODORE STEPHANIDES

POETRY

The Golden Face (London: Fortune Press, 1965)

Cities of the Mind (London: Fortune Press, 1969)

Worlds in a Crucible (London: Mitre Press, 1973)

Autumn Gleanings (Corfu: Durrell School of Corfu, 2008)

PLAY

Karaghiozis and the Enchanted Tree: a modern Greek shadow-play comedy (London: Greek Gazette, 1979)

TRANSLATIONS (*with George Katsimbalis)

– Poems by Kostes Palamas 1925.*

– Modern Greek Poems 1926.*

– C.P. Cavafy’s ‘Waiting for the Barbarians’, with Lawrence Durrell, appeared in New English Weekly 1939.

– Kostes Palamas: Three Poems 1969; privately published in an edition of 500 copies.*

– Kostes Palamas: A Hundred Voices 1976; privately published.*

– Kostes Palamas: The Twelve Words of the Gypsy [with glossary and notes] (London: Oasis Books 1974/Memphis State University Press, 1975).*

– Kostes Palamas: The King’s Flute (Athens: Kostes Palamas Institute, 1982)* [bilingual edition].

– Vinsentzos Kornaros: Erotokritos, 1984.

– Kostes Palamas, ‘Iambs and Anapaests’ and ‘Ascraeus’ in Theofanis Stravrou and Constantine Trypanis (eds.) Kostis Palamas: a portrait and an appreciation (Minneapolis: Nostos, 1985).*

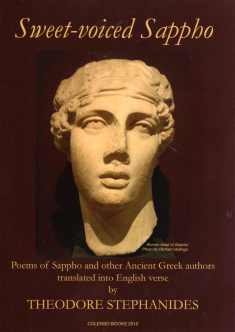

- Sweet-voiced Sappho: poems of Sappho and other Ancient Greek authors translated by Theodore Stephanides (London: Colenso Books, 2015)

SCIENTIFIC

The Microscope and the Practical Principles of Observation (London: Faber and Faber, 1947).

‘A Survey of the Freshwater Biology of Corfu and of certain other regions of Greece’, Praktika of the Hellenic Hydrological Institute 2/2 (1948) pp. 11-263.

‘Some notes on the Entomostraca of Corfu, Greece, after an interval of 23 years’, Praktika of the Hellenic Hydrological Institute 7/2 (1960), pp. 3-10.

‘The Influence of the Antimosquito Fish, Gambusia afferis, on the natural fauna of a Corfu lakelet’, Praktika of the Hellenic Hydrological Institute 9 (1964) pp. 3-6.

HISTORY

‘Synoptic History of Corfu’ in John Forte (ed.) Corfu: Venus of the Isles (Essex: East Essex Gazette, 1963).

MEMOIRS

Climax in Crete (London: Faber and Faber, 1946), foreword by Lawrence Durrell.

Island Trails (London: Macdonald, 1973), introduction by Gerald Durrell.

‘First Meeting with Lawrence Durrell’ and ‘The House at Kalami’ in James A. Brigham and Ian S. MacNiven (eds.), Deus Loci 1/1 (1977) [reprinted in Ian S. MacNiven and Carol Pierce (eds.) Twentieth Century Literature 33/3 (1987)].

‘In Egypt after the fall of Crete’ in James A. Brigham and Ian S. MacNiven (eds.) Deus Loci 3/3 (1980).

‘Days at Palaeocastritsa’ in James A. Brigham (ed.) Deus Loci 6/6 (1983).

HUMOUR

‘Bishop’s Move’ in James A. Brigham (ed.) Deus Loci 6/6 (1983).

UNPUBLISHED WORKS

‘The Bridge of Arta: a tragedy in three acts’, verse.

‘Labyrinth: a tragedy in three acts’, verse.

‘Arodaphnousa: a tragedy in three acts’, verse.

‘Karaghiozis, Alexander the Great and the Dreadful Dragon: a shadow-play in four acts’.

‘Sappho: translation of some of the extant poems’, verse.

‘Life and Death in Greek Folk-Poetry: essays and poems’.